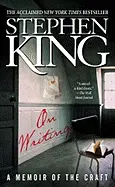

On Writing - by Stephen King

ISBN: 0743455967Date read: 2010-05-05

How strongly I recommend it: 6/10

(See my list of 430+ books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

Great thoughts about writing (mostly books) from one of the most successful writers ever. Oddly doubles as an autobiography, telling many stories about his life from childhood.

my notes

Writing is telepathy: We’re not even in the same year together, let alone the same room. Except we are together. We’re close. We’re having a meeting of the minds.

All the arts depend upon telepathy to some degree, but I believe that writing offers the purest distillation.

Writing is refined thinking.

WORKING:

Writing has always been best when it’s intimate, as sexy as skin on skin.

Stopping a piece of work just because it’s hard, either emotionally or imaginatively, is a bad idea. Sometimes you have to go on when you don’t feel like it, and sometimes you’re doing good work when it feels like all you’re managing is to shovel shit from a sitting position.

(How he knew his brother wasn't a real musician:) We never heard him taking off, surprising himself with something new, blissing himself out. And as soon as his practice time was over, it was back into the case with the horn.

If there’s no joy in it, it’s just no good. It’s best to go on to some other area, where the deposits of talent may be richer and the fun quotient higher. Talent renders the whole idea of rehearsal meaningless; when you find something at which you are talented, you do it (whatever it is) until your fingers bleed or your eyes are ready to fall out of your head. Even when no one is listening (or reading, or watching), every outing is a bravura performance, because you as the creator are happy.

The work starts to feel like work, and for most writers that is the smooch of death. Writing is at its best - always, always, always - when it is a kind of inspired play for the writer.

If no one says to you, “This is wonderful!,” you are a lot less apt to slack off or to start concentrating on the wrong thing... being wonderful, for instance, instead of telling the goddam story.

In the end, it’s about enriching the lives of those who will read your work, and enriching your own life, as well. It’s about getting up, getting well, and getting over.

ADVERBS:

When I use adverbs, it’s usually for the same reason any writer does it: because I am afraid the reader won’t understand me if I don’t. I’m convinced that fear is at the root of most bad writing.

(On adverbs:) Your man may be floundering in a swamp, and by all means throw him a rope if he is. But there’s no need to knock him unconscious with ninety feet of steel cable. Good writing is often about letting go of fear and affectation.

To write adverbs is human, to write he said or she said is divine.

GOOD WRITING:

Language does not always have to wear a tie and lace-up shoes. The object of fiction isn’t grammatical correctness but to make the reader welcome and then tell a story - to make him/her forget, whenever possible, that he/she is reading a story at all. The single-sentence paragraph more closely resembles talk than writing, and that’s good. Writing is seduction. Good talk is part of seduction.

Good writing consists of mastering the fundamentals (vocabulary, grammar, the elements of style) and then filling the third level of your toolbox with the right instruments.

If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot.

Most writers can remember the first book he/she put down thinking: I can do better than this. Hell, I am doing better than this! What could be more encouraging to the struggling writer than to realize his/her work is unquestionably better than that of someone who actually got paid for his/her stuff?

One learns most clearly what not to do by reading bad prose - one novel like Asteroid Miners (or Valley of the Dolls, Flowers in the Attic, and The Bridges of Madison County, to name just a few) is worth a semester at a good writing school.

Good writing, on the other hand, teaches the learning writer about style, graceful narration, plot development, the creation of believable characters, and truth-telling.

Being flattened is part of every writer’s necessary formation. You cannot hope to sweep someone else away by the force of your writing until it has been done to you.

Write what you like, then imbue it with life and make it unique by blending in your own personal knowledge of life, friendship, relationships, sex, and work. Especially work. People love to read about work. God knows why, but they do.

Thin description leaves the reader feeling bewildered and nearsighted. Overdescription buries him or her in details and images. The trick is to find a happy medium.

Good description usually consists of a few well-chosen details that will stand for everything else.

When a reader puts a story aside because it “got boring,” the boredom arose because the writer grew enchanted with his powers of description and lost sight of his priority, which is to keep the ball rolling.

Norris’s books provoked a good deal of public outrage, to which Norris responded coolly and disdainfully: “What do I care for their opinions? I never truckled. I told them the truth.” Some people don’t want to hear the truth, of course, but that’s not your problem. What would be is wanting to be a writer without wanting to shoot straight.

If I am able, even briefly, to give you a Wilkes’-eye-view of the world - if I can make you understand her madness - then perhaps I can make her someone you sympathize with or even identify with. The result? She’s more frightening than ever, because she’s close to real. If, on the other hand, I turn her into a cackling old crone, she’s just another pop-up bogeylady. In that case I lose bigtime, and so does the reader.

The most important things to remember about back story are that (a) everyone has a history and (b) most of it isn’t very interesting.

REWRITING:

When you write a story, you’re telling yourself the story. When you rewrite, your main job is taking out all the things that are not the story.

Write with the door closed, rewrite with the door open.

Your stuff starts out being just for you, but then it goes out. Once you know what the story is and get it right, it belongs to anyone who wants to read it. Or criticize it, if you’re very lucky.

Every book - at least every one worth reading - is about something. Your job during or just after the first draft is to decide what something or somethings yours is about. Your job in the second draft - one of them, anyway - is to make that something even more clear.

But once your basic story is on paper, you need to think about what it means and enrich your following drafts with your conclusions.

If I write rapidly, putting down my story exactly as it comes into my mind, only looking back to check the names of my characters and the relevant parts of their back stories, I find that I can keep up with my original enthusiasm and at the same time outrun the self-doubt that’s always waiting to settle in.

I don’t see themes until the story’s done. Once it is, I’m able to kick back, read over what I’ve written, and look for underlying patterns. If I see some (and I almost always do), I can work at bringing them out in a second, more fully realized, draft of the story. Two examples of the sort of work second drafts were made for are symbolism and theme.

Good fiction always begins with story and progresses to theme; it almost never begins with theme and progresses to story.

You’ll find reading your book over after a six-week layoff to be a strange, often exhilarating experience. It’s yours, you’ll recognize it as yours, even be able to remember what tune was on the stereo when you wrote certain lines, and yet it will also be like reading the work of someone else, a soul-twin, perhaps. This is the way it should be, the reason you waited. It’s always easier to kill someone else’s darlings than it is to kill your own.

WHERE TO WORK:

The biggest aid to regular production is working in a serene atmosphere.

Put your desk in the corner, and every time you sit down there to write, remind yourself why it isn’t in the middle of the room. Life isn’t a support-system for art. It’s the other way around.

It’s difficult for even the most naturally productive writer to work in an environment where alarms and excursions are the rule rather than the exception.

The space can be humble (probably should be, as I think I have already suggested), and it really needs only one thing: a door which you are willing to shut. The closed door is your way of telling the world and yourself that you mean business; you have made a serious commitment to write and intend to walk the walk as well as talk the talk. By the time you step into your new writing space and close the door, you should have settled on a daily writing goal.

Like your bedroom, your writing room should be private, a place where you go to dream.

Habituate yourself, to make yourself ready to dream just as you make yourself ready to sleep by going to bed at roughly the same time each night and following the same ritual as you go. In both writing and sleeping, we learn to be physically still at the same time we are encouraging our minds to unlock from the humdrum rational thinking of our daytime lives.

OTHER READING:

Light in August (still my favorite Faulkner novel),

The Shakespeares, the Faulkners, the Yeatses, Shaws, and Eudora Weltys. They are geniuses.

Strunk and White offer the best tools and rules you could hope for, describing them simply and clearly, with a refreshing strictness.