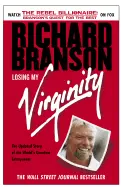

Richard Branson - by Losing My Virginity

ISBN: 0812932293Date read: 2008-06-01

How strongly I recommend it: 4/10

(See my list of 430+ books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

Autobiography of his life from childhood through 2004. Interesting how he was always over-leveraged and how that drove him forward. Amazing how he negotiated Necker Island from £3 million down to £180k.

my notes

Above all, you want to create something you're proud of. This has always been my philosophy of business. I can honestly say that I have never gone into any business purely to make money. If that is the sole motive, then I believe you are better off not doing it. A business has to be involving, it has to be fun, and it has to exercise your creative instincts.

(When selling Student:) I made the mistake of telling them all about my future plans. Fantasizing about the future is one of my favorite pasttimes. [other plans for Student:] I felt that students were given a raw deal from banks, and I wanted to set up a cheap student bank. I wanted to set up a string of nightclubs and hotels where students could stay, perhaps even offer them good travel, like student trains or a student airline. [This is when he was 20 years old.]

(1970:) I knew very little about the record industry, but from what I saw at the record shop, I could see that it was a wonderfully informal business with no strict rules. It had unlimited potential for growth : a new band could suddenly sweep the nation and be a huge hit. The music business is a strange combination of real and intangible assets: pop bands are brand names in themselves, and at a given stage in their careers they can practically guarantee hit records. But it is also an industry where the few successful bands are exceptionally rich and the bulk of the bands remain obscure and impoverished.

The rock business is a prime example of the most ruthless kind of capitalism.

I imagined that the best environment for making records would be a big, comfortable house in the country where a band could come and stay for weeks at a time and record whenever they felt like it. So during 1971 I started looking for a country house that I could convert into a recording studio. [They drove around and looked at ads and found a 15-bedroom manor for £35k but agreed to £30k because it had been on the market a while. He had no money himself but borrowd some from the family and showed the bank his business receipts, and got a loan.]

I have never enjoyed being accountable to anyone else or being out of control of my own destiny. I have always enjoyed breaking the rules, whether they were school rules or more general rules such as the idea that no 17-year-old can edit a national magazine. As a 20-year old I had lived life entirely on my own terms, following my instincts.

[When Virgin took off, with Tubular Bells, they had two options to grow: one would be paid up-front by another company who would distribute it and keep most of the profits. The other was more risky: forego up-front payment and royalties, and just pay another label to manufacture and distribute. Carry all the risk but have all the upside. That's what they chose.]

Part of the secret of running a record label was to build up a great sense of momentum, to keep signing new bands, and keep breaking them into the big time. Even if a high-profile band lost us money, there would be other intangible benefits, such as attracting others to sign with us or opening doors to radio stations for our newer bands.

I have always believed that the only way to cope with a cash crisis is not to contract but to try to expand out of it.

I normally make up my mind about whether I can trust somebody within 60 seconds of meeting them.

Necker Island - price was £3 million : Joan and I were determined to buy Necker. I found out the owner wanted to sell in a hurry. He wanted to build something in Scotland that would cost him £200k. I upped my offer to £175k and held on for 3 months. Finally I got a call saying, "If you offer £180k, it's yours." The government required he build a resort within 5 years. I was determined to make the money to be able to afford it.

Travellers stranded trying to get to Puerto Rico after a cancelled flight. I made a few calls to charter companies and agreed to charter a plane to PR for $2k. Divided the price by the number of seats and wrote, "Virgin Airways, $39 single flight to Puerto Rico." Walked around the terminal and soon filled every seat on the charter plane.

Whenever Virgin has money, I always renew my search for new opportunities. I am always trying to broaden the group so that we are not dependent upon a narrow source of income, but I suspect that this is due more to inquisitiveness and restlessness than sound financial sense.

(When "Event" magazine failed:) I realized how important it was to separate the various Virgin companies so that if one failed, it would not threaten the rest of the Virgin group.

(When Virgin Records was doing well:) As I watched the money pour into the bank, I began to think of other ways to use it. I needed another challenge. I had the opportunity to use our cash to set up more Virgin companies and widen the basis of the group so that all our eggs would not be in one basket if we were hit by another recession. I also wanted to expand the Virgin name to stand for more than a record label and become more widely involved in all kinds of media. I had cash mounting up in the bank, and I wanted to reinvest it as fast as possible.

I make up my mind about a business proposal within 30 seconds and whether it excites me. I rely far more on gut instinct than researching huge amounts of statistics. I feel numbers can be twisted to prove anything.

I found the press enjoyed writing stories about Virgin if they could put a face to the name. For the first time I began to use myself to promote the companies and the brand. Apart from never involving my family, I was happy to do anything to increase Virgin's profile: promotion was one of the keys to our growth.

(About CD-burning machines:) I was determined that this example of vertical integration would work in the same way as the integration between owning a recording studio, a record label, and record shops had worked. I have a weakness for vertical integration, which I admit does not always work. (Mistakes: CD factory, bought a pub because so many Virgin staff went there. Almost bought a property maintenance company because they had so many properties that needed repair.)

We reverted to our old (and current) way of doing business : minimize the amount of cash we have tied up in fixed assets and buy services from the most efficient supplier.

Whenever anyone tells me that I've got no option, I try to prove them wrong.

Since 1993, we've had the luxury of money and a strong brand name that could be lent to a wide variety of businesses.

I could have retired, but this was fun. Fun is at the core of how I like to do business, and it has informed everything I've done from the outset. More than any other element, fun is the secret of Virgin's success.

I'm often asked to define my business philsophy, but I don't believe that it can be taught as if it's a recipe. There aren't ingredients and techniques that will guarantee success. Parameters exist that, if followed, will ensure that a business can continue, but it's not as if you can clearly define our business succes and then bottle it as if it's a perfume.

It's not that simple. To be successful, you have to be out there, you have to hit the ground running, and if you have a good team around you and more than a fair share of luck, you might make something happen.

Virgin has made money, but I have always invested it in new projects to keep the company growing. As a result, we rarely had the luxury of spare cash to use as a cushion.

My vision for Virgin has never been rigid, and changes constantly, like the company itself.

I have always lived my life by making lists : lists of people to call, lists of ideas, lists of companies to set up, lists of people who can make things happen. Each day I work through these lists, and that sequence of calls propels me forward.

Despite employing over 20,000 people, Virgin is not a big company - it's a big brand made up of lots of small companies.

Our priorities are the opposite of most competitors, who worry about shareholders first, customers next, employees last. For us, employees matter most. Start off with a happy well-motivated workforce, you're far more likely to have happy customers.

Every time one of our ventures gets too big, we divide it up into smaller units. I go to deputy directors and tell them they're now directors of a new company. The people haven't had much more work to do, but they have a greater incentive to perform and a greater zest for their work. By the time we sold Virgin Music, we had as many as 50 subsidiary record companies, and not one of them had more than 60 employees.

Once you have a great product, it's essential to protect its reputation with vigilance. (Monitor the press.)

By investing in separate businesses with partners, "ring-fenced" as the bankers keep telling me, we had been able to withstand the management pressures of 9/11, spread risk and make what we hope have been a lot of good decisions. Couple those with a venture-capital private-equity model of creating individual companies with their own business cases, shareholders, and financial resources, and you have the Virgin of 2004.