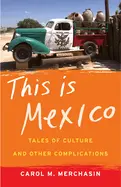

This Is Mexico - by Carol Merchasin

ISBN: 1631529625Date read: 2024-05-15

How strongly I recommend it: 5/10

(See my list of 430+ books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

Day-to-day insights from an American lawyer who moved to Mexico. Read in preparation for travel.

my notes

Nowhere in the world do two countries as different as Mexico and the United States live side by side.

Mexican philosophy on imperfection is captured by the expression ni modo, loosely translated as, “Well, what can you do?” accompanied by a shrug.

Another useful phrase in describing life’s imperfections is no pasa nada, which means “nothing happened” or “no worries.”

It is difficult to distinguish between wise compassion and idiot compassion, where good intentions merge with guilt.

Mexicans love formality, courtesy, and ceremony.

Nod your head deeply. Make eye contact and smile as you pass.

Sing out, “Buenos días, señor,” forcefully, with feeling.

Buenos días has a precise shelf life - it ends at noon.

At noon, switch to buenas tardes,

Sundown, move to buenas noches.

Titles. Men are señor; unmarried women, or those whose status you don’t know, are señorita; and known, married women are señora.

Older people are don and doña.

Titles are important here.

46 percent of the population are classified as poor.

Add in those who lack access to one or more of these services, or because they are very close to the poverty line, and it is estimated that the number of Mexico’s poor soars to an astronomical 80 percent.

“For twelve thousand pesos, the city workers come out one day to dig the trench and hook up the water pipes, and I pay the city.

For thirty-five hundred pesos, the same men come out at night, I help them dig the trench, they hook up the water pipes, and I pay them.”

This “midnight service system” is very popular in Mexico. When the cable repairmen came to our house, they noticed we did not have “premium” service.

They offered to come that night to install a black box that would allow us to circumvent the cable company, also known as their employer.

In a country where most utilities are regarded as ineffective, inefficient, and corrupt, Mexicans feel a certain justice in doing whatever is necessary to avoid payment.

Mexico does not have enough money to make change.

United States has too much money to want change.

“If you are not content with what you have, you would not be satisfied if it were doubled.”

Mexicans are culturally more content with what they have.

Lupe’s tiny restaurant has six tables filled to overflowing.

I sit watching her two young sons run up to the kitchen door, carrying a plastic bag with three or four bottles of mineral water.

A little later, I see them with a bottle of tequila.

Limes, tortillas, dish soap, and other mysterious bags follow over the course of our ninety-minute meal.

I begin to wonder if Lupe is pathologically disorganized.

Who waits to buy what she needs until the middle of the evening rush?

Three decades ago, the Japanese were hailed for popularizing just-in-time (JIT), a manufacturing inventory system. Factories bought what they needed only when they needed it and saved millions.

Lupe, like most small-business owners, runs a JIT restaurant.

With cheap labor - nothing is much cheaper than your own sons - and a 150-square-foot neighborhood store giving credit until tomorrow, the process works.

Mexicans work more than any of the world’s twenty-nine advanced economies.

Mexicans worked 595 minutes a day, just short of ten hours.

Japan weighed in at 540 minutes

Canada at 517

United States at 496.

The study included unpaid work, adding in Mexican women who toiled a whopping four hours and thirteen minutes a day in chores like cooking and cleaning.

The United States spent the least amount of time in the world on unpaid work like cooking and cleanup - a scant thirty minutes per day.

Lawyers’ job is to keep bad things from happening to our clients.

And if bad things do happen, our job is to make it clear who will pay.

Sixty-five percent of Mexicans do not use a bank.

Tanda: flexible, communal arrangement, used as a way to meet their short-term financial needs.

If I want to start a tanda, it may be because a big expense is coming.

I can recruit others who want to save money for something.

I choose the term of the time commitment (say, ten weeks), the contribution (one hundred pesos a week, for example), and when I want to take my payout (often week one). In week one, I take in nine hundred pesos from my nine participants, plus my own one hundred pesos, and - ¡qué bueno! - I have one thousand pesos to buy the school uniforms.

After I take my payout, I continue to pay in one hundred pesos a week, as does everyone else. Whoever has drawn week two takes the next one thousand pesos, and on it goes. Tandas are flexible - they can be for shorter or longer periods of time, with higher or lower weekly contributions.

The glue that holds a tanda together is a community of people who have personal relationships with and trust one another.

Mexican cultural value of deference and personal dignity. Visible demonstrations of civility are required.

Endless iterations of buenas tardes, que le vaya bien, may your children do well, may your health be perfect.

Respect, expressed through politeness, is valued over all other personal characteristics.

“You are a person of intelligence? Nice, but how are your manners?”

“You are ethical? Good, but are you maintaining the social order of the group?”

The unconscious question for Mexicans is, “What do I need to do to serve these people who are my support?”

Mexicans adhere first to family, then to extended family, and then to a community.

Mexicans spend time relaxing, hanging out with family and friends - activities that have value, an investment in something that matters; it is not time wasted.

Unless it’s necessary, many do not want to trade time for money.

Mexican laws are not passed to be enforced consistently, if at all. They are aspirational.

Mexicans use a number of nonresponsive and unusual linguistic work-arounds to limit risk.

Do not be completely honest with anyone who has more power than you.

Do not offer information that is not specifically asked for.

Use a lot of effusive language.

Learning to work with this system requires a high level of precision.

If I call the swimming pool to find out if they are open, they may say yes, but when I arrive, there may be no water in the pool.

The next week, I may call again and wisely ask, “Are you open and do you have water in the pool?” They may say, “Sí, sí” but when I arrive there might be only a paltry puddle

Hope he will come tomorrow; wait until he does - two concepts that are, conveniently enough, expressed by the same verb, esperar.

IN 1968, 96 percent of Mexicans identified as Catholic, women bore an average of seven children, and Catholicism was a growth business.

Today, a fertility rate of 2.2.

Today, only about 83 percent of Mexicans identify as Catholic.

No state religion exists here.

From birth to death, Mexican family life is a rhythm of rituals marked by fiestas.

Mariachi music snowballed in popularity after the 1917 revolution when the Mexican government began to try to forge a new cultural identity.

Fiestas are our only luxury.