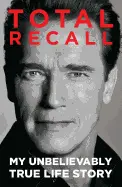

Total Recall - by Arnold Schwarzenegger

ISBN: 1410452107Date read: 2016-05-05

How strongly I recommend it: 8/10

(See my list of 430+ books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

I was not expecting to love this so much! I'm not a fan of his, but MAN his ambitious mindset, especially in his early days when he first moved to America, is so inspiring. Both on the movie-star side and real-estate side. If you need a role model or inspiration for thinking big, this is it. (Skip the final section on his governor days.) I was telling friends stories and thoughts about this book for weeks afterwards.

my notes

After the turmoil of the war, my parents’ big desire was for us to be stable and safe.

We were growing up among men who felt like a bunch of losers. Their generation had started World War II and lost.

My dad's answer to life was discipline. We had a strict routine that nothing could change: sports, exercises were added to the chores, and we had to earn our breakfast by doing sit-ups. In the afternoon, we’d finish our homework and chores, and my father would make us practice soccer no matter how bad the weather was. If we messed up on a play, we knew we’d get yelled at.

My father believed just as strongly in training our brains. Visiting another village, maybe, or seeing a play. Then in the evening we had to write a report on our activities, ten pages at least. He’d hand back our papers with red ink scribbled all over them, and if we had spelled a word wrong, we had to copy it fifty times over.

He had no patience with our problems. If we wanted a bicycle, he’d tell us to earn the money for it ourselves. I never felt that I was good enough, strong enough, smart enough. He let me know that there was always room for improvement. A lot of sons would have been crippled by his demands, but instead the discipline rubbed off on me. I turned it into drive.

We were also supercompetitive the way brothers often are - always trying to outdo each other and win the favor of our dad. I was always on the lookout for ways to gain the advantage.

I fought back my fear mainly because I had to prove that I was stronger. It was extremely important to show my parents I am brave.

Somehow the thought took shape in my mind that America was where I belonged. Nothing more concrete than that. Just . . . America. I became absolutely convinced that I was special and meant for bigger things. I knew I would be the best at something - although I didn’t know what - and that it would make me famous. America was the most powerful country, so I would go there. The thought of going to America hit me like a revelation, and I really took it seriously. I’d talk about it. The kids got used to hearing me talk about it and thought I was weird, but that didn’t stop me from sharing my plans with everyone: my parents, my teachers, my neighbors.

The idea of balancing the body and the mind was like a religion for him. “You have to build the ultimate physical machine but also the ultimate mind,” he would say. “Read Plato! The Greeks started the Olympics, but they also gave us the great philosophers, and you’ve got to take care of both.”

Even though I appreciated the example of my father with the discipline and the things that he accomplished professionally, in sports, with the music, the very fact that he was my father took away from its significance for me. All of a sudden, I had a whole new life, and it was mine.

What the article said: It gave Reg’s whole life story, from growing up poor in Leeds, England, to becoming Mr. Universe, getting invited to America as a champion bodybuilder, getting sent to Rome to star as Hercules, and marrying a beauty from South Africa, where he now lived when he wasn’t training on Muscle Beach. This story crystallized a new vision for me. I could become another Reg Park. All my dreams suddenly came together and made sense. I’d found the way to get to America: bodybuilding! And I’d found a way to get into movies. They would be the thing that everyone in the world would know me for.

I refined this vision until it was very specific. I was going to go for the Mr. Universe title; I was going to break records in power lifting; I was going to Hollywood; I was going to be like Reg Park. The vision became so clear in my mind that I felt like it had to happen. There was no alternative; it was this or nothing.

The deltoids were screaming from the unexpected sequence of sets. I’d shown them who was boss. Their only option now was to heal and grow.

I never went to a competition to compete. I went to win. Even though I didn’t win every time, that was my mind-set. I became a total animal. If you tuned into my thoughts before a competition, you would hear something like: “I deserve that pedestal, I own it, and the sea ought to part for me. Just get out of the fucking way, I’m on a mission. So just step aside and gimme the trophy.” I pictured myself high up on the pedestal, trophy in hand. Everyone else would be standing below. And I would look down.

I was already the favorite to win the 1967 Mr. Universe competition. But that didn’t feel like enough - I wanted to dominate totally. If I’d wowed them with my size and strength before, my plan now was to show up unbelievably bigger and stronger and really blow their minds.

I learned the advantage of training early, before the day starts, when there are no other responsibilities and nobody else is asking anything of you.

The limit I thought existed was purely psychological. Now that I’d seen someone doing a thousand pounds, I started making leaps in my training. It showed the power of mind over body.

I thought more about my loss to Frank Zane. I could have found a way to train more even without access to equipment: I hadn’t done everything in my power to prepare. I decided, wouldn’t be an amateur ever again. Now the real game would begin.

It’s human nature to work on the things that we are good at. It’s so satisfying. To be successful, however, you must be brutal with yourself and focus on the flaws. That’s when your eye, your honesty, and your ability to listen to others come in.

I always wrote down my goals. It wasn’t sufficient just to tell myself “lose twenty pounds and learn better English and read a little bit more.” No. That was only a start. Now I had to make it very specific so that all those fine intentions were not just floating around. I would take out index cards and write that I was going to: • get twelve more units in college; • earn enough money to save $5,000; • work out five hours a day; • gain seven pounds of solid muscle weight; and • find an apartment building to buy and move into.

Knowing exactly where I wanted to end up freed me totally to improvise how to get there.

I always saw myself as a citizen of the world.

Over the next two or three years, I did research. Every day I would look at the real estate section in the newspaper, studying the prices and reading the stories and ads. I got to where I knew every square block of Santa Monica. I knew how much the property values increased north of Olympic Boulevard versus north of Wilshire versus north of Sunset. I understood about schools and restaurants and proximity to the beach. I knew every building in town. I knew every transaction: who was selling, at what price, how much the property had appreciated since it last changed hands, what the financial sheet looked like, the cost of yearly upkeep, the interest rate on the financing. I met landlords and bankers. The math of real estate really spoke to me. I could tour a building, and as I walked through it, I would ask about the square footage, the vacancy factor, what it would cost per square foot to operate, and quickly calculate in my mind how many times the gross I could afford to offer and still be able to make the payments.

Seeing me pull off a $215,000 deal left my old friend Artie Zeller in shock. For days afterward, he kept asking how I had the balls to do it. He could not understand because he never wanted any risk in his life. “How can you stand the pressure? You have the responsibility of renting out the other five units. You have to collect the rent. What if something goes wrong?” Problems were all he could see. It could be terrible.

“Artie, you almost scared me just now.” I laughed. “Don’t tell me any more of this information. I like to always wander in like a puppy. I walk into a problem and then figure out what the problem really is. Don’t tell me ahead of time.” Often it’s easier to make a decision when you don’t know as much, because then you can’t overthink. If you know too much, it can freeze you. The whole deal looks like a minefield.

I’d noticed the same thing at school. Our economics professor was a two-times PhD, but he pulled up in a Volkswagen Beetle. I’d had better cars for years by that time. I said to myself, “Knowing it all is not really the answer, because this guy is not making the money to have a bigger car. He should be driving a Mercedes.”

“Just let me stumble into it,” I told them. “I don’t want to be forewarned.” You can overthink anything. There are always negatives. The more you know, the less you tend to do something. If I had known everything about real estate, movies, and bodybuilding, I wouldn’t have gone into them. I felt the same about marriage; I might not have done it if I’d known everything I’d have to go through.

Lucy gave me advice about Hollywood. “Just remember, when they say, ‘No,’ you hear ‘Yes,’ and act accordingly. Someone says to you, ‘We can’t do this movie,’ you hug him and say, ‘Thank you for believing in me.’ ”

I’d been bodybuilding for twelve years already, and the philosophy of the movie spoke to me. I liked the idea of staying hungry in life and never staying in one place.

I wanted to be good enough at something else to be recognized again, and even bigger than before.

They needed me to lose weight. First I had to redo myself mentally - let go of the 250-pound image of Mr. Olympia that was in my head. I started visualizing myself instead as lean and athletic. And all of a sudden what I saw in the mirror no longer fit. Seeing that helped kill my appetite for all the protein shakes and all the extra steak and chicken I was used to. I pictured myself as a runner rather than a lifter, and changed around my whole training regimen to emphasize running, bicycling, and swimming rather than weights. All through the winter, the pounds came off, and I was pleased.

Hearing them talk about the need to disconnect and refresh the mind was like a revelation. “Arnold, you’re an idiot,” I told myself. “You spend all this time on your body, but you never think about your mind, how to make it sharper and relieve the stress. When you have muscle cramps, you have to do more stretching, take a Jacuzzi, put on the ice packs, take more minerals. So why aren’t you thinking that the mind also can have a problem? It’s overstressed, or it’s tired, it’s bored, it’s fatigued, it’s about to blow up - let’s learn tools for that.” They gave me a mantra and taught me to use a twenty-minute meditation session to get to a place where you don’t think. They taught how to disconnect the mind, so that you don’t hear the clock ticking in the background or people talking. If you can do this for even a few seconds, it already has a positive effect. The more you can prolong that period, the better it is.

She was a normal person who wanted normal things, and there was nothing normal about me. My drive was not normal. My vision of where I wanted to go in life was not normal. The whole idea of a conventional existence was like Kryptonite to me.

I knew the way my mind worked, and that to accomplish anything, I had to buy in completely. The goal had to be something that made total sense and that I could look forward to every day, not just something I was doing for money or some other arbitrary reason, because then it wouldn’t work.

I got to know Nicholson, Beatty, and the rest of the Mulholland Drive. I was not inside enough to be partying with them all the time, but I did get exposed to how stars at that level lived and operated, what they were into, and how they moved around, and it inspired me to be there myself in a few years.

Whoever represented me had to buy into the big vision.

They wanted me to play a Nazi officer, a wrestler, a football player, a prisoner. I never took jobs like that because I would say to myself, “This isn’t going to convince anybody that you’re here to be a star.”

But I felt that I was born to be a leading man. I had to be on the posters, I had to be the one carrying the movie.

The only way you become a leading man is by treating yourself like a leading man and working your ass off.

People of her caliber have the social skills to make it seem like they are very much aware of you and that they know a lot about what you are doing.

The lawyer announced, “Dino doesn’t want to give you five points, like it says in the contract. He wants to give you no points.” I said, “Take the points. I’m in no position to negotiate. Because that’s not what I’m doing the movie for.” I understood the reality. The situation was lopsided. Dino had the money, and I needed the career, so it made no sense to argue. It was just supply and demand. But, I also thought, the day will come when the tables will turn, and Dino will have to pay.

I felt like my movie career had suddenly come into sharp focus. The vision had always been there, but hazy: I never knew which direction it would go or how I was going to get the big break. But being chosen for Conan was like winning my first international bodybuilding title. Until then I could see my progress in the mirror, I could see my muscles slowly grow, but I really never knew where I stood. Then, after winning Mr. Universe, I thought, “Jesus, that was international judging, and I was competing against guys I see in the magazines, and I won. I’m going to succeed.”

She told me instantly that the whole thing was a mistake. What’s your goal in doing this?” I had to admit I had no answer to that. I’d just been in a silly mood and said to Ara, “Let’s do something funny.” I wasn’t trying to get anything out of it. “Well, since there’s no goal and it’s not going to lead anywhere, kill it. You don’t need it. You had your fun, now move on.”

She was wise about public perception because that was the world in which she’d grown up.

Maria was the first girlfriend I ever had who didn’t treat my ambitions as an annoyance, some kind of madness that interfered with her vision of the future: namely, marriage, kids, and a cozy little house somewhere - and the stereotypical all-American life. Maria’s world wasn’t small like that. It was gigantic.

I’d finally met a girl whose world was as big as mine. I’d reached some of my goals but a lot of my world was still a dream. And when I’d talk about even bigger dreams, she never said, “Come on, this can’t be done.” She’d seen it happen in her family.

She understood why I had to get up at six in the morning to train for two hours, and she’d come with me to the gym. At dinner she’d see me about to dig into some ice cream, and she’d literally take it away.

In politics, when disputes arise and camps form, you have to grasp what’s happening and move very quickly. She was right there with lightning-fast perceptions and really good advice. She talked to the right people and helped me avoid getting isolated or blindsided. She was a total animal.

I saw myself as a businessman first.

Very few actors like to sell. I’d seen the same thing with authors in the book business. The typical attitude seemed to be, “I don’t want to be a whore. I create; I don’t want to shill. I’m not into the money thing at all.” It was a real change when I showed up saying, “Let’s go everywhere, because this is good not only for me financially but also good for the public; they get to see a good movie!”

I wanted to be involved in the meetings. I wanted everyone to see that I was working very hard to create a return on the studio’s investment.

For me work just meant discovery and fun. If I heard somebody complaining, “Oh, I work so hard, I put in ten- and twelve-hour days,” I would crucify him. “What the fuck are you talking about, when the day is twenty-four hours? What else did you do?”

I loved the variety in my life. One day I’d be in a meeting about developing an office building or a shopping center, trying to maximize the space. The next day I’d be talking to the publisher of my latest book about what photos needed to be in it. Next I’d be working with Joe Weider on a cover story. Then I’d be in meetings about a movie. Or I’d be in Austria talking politics with Fredi Gerstl and his friends. Everything I did could have been my hobby. It was my hobby, in a way. I was passionate about all of it. My definition of living is to have excitement always; that’s the difference between living and existing. I seldom saw my life as hectic.

When I wanted to know more about business and politics, I used the same approach I did when I wanted to learn about acting: I got to know as many people as I could who were really good at it.

I never like to cut things from my life, I only add.

“Now that studios are coming to me,” I said to myself, “what if I go all out? Really work on the acting, really work on the stunts, really work on whatever else I need to be onscreen. Also market myself really well, market the movies well, promote them well, publicize them well. What if I shoot to become one of Hollywood’s top five leading men?”

Because there was so little room at the top of the ladder, people got intimidated and felt more comfortable staying on the bottom of the ladder. But, in fact, the more people that think that, the more crowded the bottom of the ladder becomes! Don’t go where it’s crowded. Go where it’s empty. Even though it’s harder to get there, that’s where you belong and where there’s less competition.

So there would be plenty of work - and plenty of opportunity to become as big a star as any of them. I wanted to be in the same league and on the same pay scale. As soon as I realized this, I felt a great sense of calm. Because I could see it.

I’m always comparing life to a climb, not just because there’s struggle but also because I find at least as much joy in the climbing as in reaching the top.

You should wait to marry until you are set financially and the toughest struggles of your career are behind you.

Whenever I finished filming a movie, I felt my job was only half done. Every film had to be nurtured in the marketplace. You can have the greatest movie in the world, but if you don’t get it out there, if people don’t know about it, you have nothing. It’s the same with poetry, with painting, with writing, with inventions. It always blew my mind that some of the greatest artists, from Michelangelo to van Gogh, never sold much because they didn’t know how. They had to rely on some schmuck - some agent or manager or gallery owner - to do it for them. Picasso would go into a restaurant and do a drawing or paint a plate for a meal. Now you go to these restaurants in Madrid, and the Picassos are hanging on the walls, worth millions of dollars. That wasn’t going to happen to my movies. Same with bodybuilding, same with politics - no matter what I did in life, I was aware that you had to sell it.

What we were proposing was an offbeat picture by three expensive guys. If each of us got paid his going rate, the budget would be so top-heavy that we thought no studio would touch it. And yet none of us wanted to take a pay cut because working for less can hurt your negotiating power in future deals. So when we pitched Tom Pollock, the head of Universal, we proposed to make Twins for no salary at all. Zero. What we wanted in exchange was a piece of the movie: a percentage of the box-office receipts, video sales and rentals, airline showings, and so on.

I thought about what I had that those kids didn’t. I grew up poor too. But I had a fire inside of me to succeed and two parents who pushed me and taught me discipline. I had a strong public school education. I had after-school sports with coaches and training partners who were role models. I had mentors who told me, “You can do it, Arnold,” and then made me believe it. They were around me twenty-four hours a day, supporting me and making me grow. But how many inner-city kids had those tools? How many learned the discipline and determination? How many got the encouragement that would let them even glimpse their self-worth? Instead, they were told they were trapped. They could see that most of the adults around them were trapped.

The most important thing was not how much you make, but how much you invest, how much you keep. I never wanted to join the long list of famous entertainers and athletes who wiped out financially.

No matter what you do in life, you have to have a business mind and educate yourself about money. You can’t just delegate it to a manager. I wanted to know the details.

My old motto: “Take one dollar and turn it into two.”

I wanted big investments that were interesting, creative, and different. Conservative bets - the kind that would generate 4 percent a year, say - didn’t interest me. I could tolerate big risks in exchange for big returns, and I would want to know as much as possible about what was going on.

As is so often the case, something that is impossible slowly becomes possible.

I always told Ronda and Lynn, “Never share my calendar with anybody,” and I would tell Maria only a few days in advance. I’m a person who does not like to talk about things over and over. I make decisions very quickly, I don’t ask many people for opinions, and I don’t want to think too many times about the same thing. I want to move on.

As a kid, as I learned about math, it all made sense. The decimals made immediate sense. The fractions made immediate sense. I knew all the roman numerals. You could throw problems at me, and I’d solve them. You could show me statistics, and instead of glazing over the way a lot of people do, I’d make out facts and trends that the figures were pointing to and read them like a story. I taught our kids math drills that my father had used on Meinhard and me. He always made us start them a month before school, and we had to do them every day because he felt that the brain has to be trained and warmed up like the body of an athlete.

I’d gotten a college education while I was a bodybuilding champ. I’d married Maria in the middle of filming Predator. I’d made Kindergarten Cop and Terminator 2 and launched Planet Hollywood while I was the president’s fitness czar.

I love it when people say that something can’t be done. That’s when I really get motivated; I like to prove them wrong. And I liked the idea of working on something bigger than me.

California! It is the place where everyone in the world wants to go. You never hear anyone from abroad say, “Oh, I love America! I can’t wait to get to Iowa!” Or “Gosh, can you tell me about Utah?” Or “I hear Delaware is a great place.” California was wrapped in problems, but it was also heaven.

Never follow the crowd. Go where it’s empty. When every immigrant I knew was saving up to buy a house, I bought an apartment building instead. When every aspiring actor was trying to land bit parts in movies, I held out to be a leading man. When every politician tries to work his or her way up from local office, I went straight for the governorship. It’s easier to stand out when you aim straight for the top.

No matter what you do in life, selling is part of it.

Don’t overthink. If you think all the time, the mind cannot relax. The key thing is to let both the mind and the body float. And then when you need to make a decision or hit a problem hard, you’re ready with all of your energy.

By not analyzing everything, you get rid of all the garbage that loads you up and bogs you down. Turning off your mind is an art. It’s a form of meditation.

Forget plan B. Think about the worst that can happen if you fail. How bad would it be?

The day has twenty-four hours. I once gave a talk in a University of California: “as a student I’d trained five hours a day, gone to acting classes four hours a day, worked in construction several hours a day, and gone to college and done my homework. And I was not the only one.”

We wrote down our training program each day. I always had the visual feedback of “Wow, an accomplishment. I did what I said I had to do. Now I will go for the next set, and the next set.” Writing out my goals became second nature, and so did the conviction that there are no shortcuts. Whether you’re doing a bicep curl in a chilly gym or talking to world leaders, there are no shortcuts - everything is reps, reps, reps. No matter what you do in life, it’s either reps or mileage.

Today I hail the fact that I didn’t have anything that I wanted in Austria, because those were the very factors that made me hungry.

Stay hungry. Be hungry for success, hungry to make your mark, hungry to be seen and to be heard and to have an effect. And as you move up and become successful, make sure also to be hungry for helping others. Don’t rest on your laurels.

If you feel a desire to do more, then go all out.